(Hey, if you want to come work with me at Roundforest, and try out JSDoc typing, feel free to find me on LinkedIn or on Twitter (@giltayar))

TypeScript! For me, it’s a love-hate relationship.

I started my developer life in statically typed languages (well, if we ignore Basic, which is dynamically typed): C, C++, and Java. Then somewhere around 2010, I had the good fortune to start working in Python. And I saw the light! I was liberated! Suddenly all those Java and C++ design sessions, where we fretted and worried and analyzed our class hierarchy to death, disappeared. I suddenly saw them for what they were: hair splitting and yak shaving about this design or that design, instead of just, well, working. And that yak shaving also usually generated tons of abstractions, that half a year later, when reading the code, were all but incomprehensible.

And then I started programming in Python, and all those discussions just end. You just work. And it’s not that the design doesn’t happen, but somehow, once you stop talking about class hierarchy, you start dealing with the data flow, dealing with what data you have in the system, and how it changes over time, and what the algorithms are that change it. And because you’re dealing with data, and not trying to abstract it away, then the design becomes simpler. Much easier to reason and deal with. And much less hair splitting. And when disagreement happens, it was on a much more practical level.

The disappearance of types was good for my profressional career. And this goodness continued when I started working in JavaScript. And one of the more interesting benefits I found for dynamic typing was that I found myself writing more tests than I usually write. This was because dynamic typing doesn’t give the safety net that static typing does. So you write more tests. Which is a good thing.

Another good thing about dynamic typing: my code was “clean”. In many ways, type information is noise that you usually don’t need to understand the code. And with dynamic typing, that noise goes away, and your code is “clean”: pure intent.

But I have to admit: While I loved having my code clean of types, I sometimes missed code completion, and the ability to know what a function accepts or returns. I didn’t worry or fret about it, and not bugs were caused by this, because if I mixed my types, my tests would tell me that, but unfortunately that happens during the running of my testis and after coding, so some amount of time was wasted to deal with problems my tests found that I would have found out during coding time if I had static typing.

But when I weighed the drawbacks of static typing (as I knew it), with the benefits of dynamic typing, I knew that I wanted stick with dynamic typing. “Never go back!”, said I. So I didn’t very much like TypeScript’s rise in popularity. It was like finally I found a nice comfortable dynamic language, and, well, just when I thought I was out, they pull me back in!

TypeScript’s gaining popularity was an affront to my belief that static typing is a scourge on the world of development and that everybody should move to dynamic typing! How can developers choose to go back to static typing after they saw the horrors of static typing? I really couldn’t understand it. And I fought back. In any forum I could—I warned of the dangers of static typing, and reminded people that if we weren’t careful, Java-isms would come and take us back to the dark ages of yak shaving and incomprehensible abstractions.

But after a while I calmed down, and I started thinking a bit. And I noticed two things. The first was that the war I was fighting was a religious war. A binary war, a holy war. And I do not like religious wars. And here I was, fighting one, feverishly, passionately, arguing against something that I had no experience about. And that was not nice. I let my anger obscure my objectivity.

The second thing I noticed was that a lot of people that I admired were using TypeScript, and liking it. So it couldn’t be all bad could it? Then again, a lot of those people did not have any experience with static typing, so maybe they were lured by the temptation of static typings, but once there, they would start to convert it to code that shaved yaks and generated incomprehensible abstractions?

Maybe. But maybe maybe I should do what I should have done from the beginning, instead of starting a holy war? Mayb I should just…

Listen.

So I talked to some TypeScript developers. And read blog posts. And realized something I never realized: TypeScript’s type system is NOT Java’s. TypeScript’s spirit is much closer to JavaScript’s than to Java’s or C#'s. How so? TypeScript’s type system is just a formal definition of something that was never really defined: JavaScript’s type system. It does not try to bend JavaScript to its type system. Rather, it tries to bend itself to JavaScript’s. I believe it’s goal is to be able to define a type signature for every NPM package out there, however weird that NPM package is. And it’s succeeding marvelously!

And that is the main argument against my “you’re going to turn JavaScript into Java” war. Typescript is not trying to emulate an OOP type system’s like Java. Not at all. It’s trying to formalize JavaScript’s informal way of implementing APIs and package interfaces. And since most JavaScript packages interface are more concerned with data, and less with abstractions, then so does TypeScript’s. Yes, you can abuse TypeScript (and JavaScript!) to create incomprehensible abstractions, but the spirit of TypeScript doesn’t really want you to do that. Instead, it encourage’s a JavaScript like simplicity, that is more around functions and data than it is around classes and abstractions.

But what about my second problem with TypeScript? Transpilation. I dislike transpilation. It… complicates everything: debugging, stack traces, tooling, comprehension, scripting. Everything. So while I was curious TypeScript, and could see the benefits, I didn’t really want to deal with that problem.

But, still, one should try, right? Right. So, because at work we work with Microservices, I decided to write my next Microservice in TypeScript. Just to try it out. Which I did.

And it was wonderful and horrible at the same time. Wonderful, because types really do help the coding phase. They don’t reduce bugs, because I have tests for that, and any typing mistakes I made would have been caught by those tests. But they do reduce the coding time, because no more typing mistakes (mostly), and they do increase the readability of the code.

Horrible? Yes. TypeScript is the only language I know that changes its behavior based on a config file. In actuality, TypeScript is not one language. It’s an infinity of languages, each one slightly different, and each one “generated” by a specific configuration file. And to figure out the language variation you want, you start playing with that arcane config file. Documentation for the configuration? It’s there, and much better than it was a year ago, but it’s still arcane.

And it was horrible because of the transpilation. I had to start figuring out the tooling. And how to work with Docker. And debugging. And stack traces. Not a nice environment. Workable, but less than perfect.

The dilemma #

So on the one side, JavaScript: wonderful language, no build time, really great tooling. And dynamically typed, with all the pros and cons that come with this. And on the other side, TypeScript: a variation on JavaScript, statically typed, altough as dynamic as you want it to be. And transpiled, with all the cons that come with this (no, there are no pros to transpilation).

So what to choose for a new project? I’ve just joined a new company, and I’d like to figure out what to use there! My heart went for JavaScript and it’s buildless simplicitiy, but I could not forget how nice static typing works when coding, and how it helps the readability of the code. But I couldn’t help myself: I dislike transpiling. I didn’t want to lose the simplicity that comes with no build phase.

So can I get both? Can I get the buildless, no transpiling simplicity of JavaScript, along with the ability to statically type functions and classes?

The answer it seems, is yes. And this blog post is all about that: how to enable this solution in your code.

Note: this solution works in Node.js. I haven’t yet tried it with frontend code, but I’m pretty sure the results will be similar.

The solution #

The solution? Good ol’ JSDocs. Ironically enough, JSDocs are an evolution of JavaDocs, which were invented in Java land as a way to document Java code, and to make it available as structured documentation.

But this time, we’re not going to use them to document JavaScript code, but rather only the types in our code. And to do that, we’re going to not simply write JSDoc comments, but write them in a way that is recognized by TypeScript. Let’s start.

By the way, you can find all the code in this blog post at the jsdode-typing repo

https://github.com/giltayar/jsdoc-typing, that includes the source for an NPM package

that has full typings and can be used with any TypeScript (or JSDoc typing) code.

Simple JSDocs #

Let’s start with a simple example of JavaScript code that is typed:

function add(a, b) {

return a + b

}

module.exports = { add }(the above code uses CommonJS, but you can also use the new native ESM supprot in Node.js)

The above code is simple: it defines a function, add, that adds two numbers. Simple JavaScript,

no types. Now let’s add some JSDocs.

/**

* @param {number} a

* @param {number} b

*/

function add(a, b) {

return a + b

}

module.exports = {

add,

}Same code, but we added a comment above the function add that defines the types of a and b.

Is this code regular JavaScript? Yes. We just added some comments.

Those comments are JSDocs typing comments. Let’s look at the JSDoc:

- It starts with

/**to tell the world that this is a JSDoc. - It includes a line for each param in the format:

/**

* @param {<type>} <paramName>

* /- The type MUST be inside

{...}and anything inside it defines what type the parameter is. - If TypeScript is used to interpret the JSDoc, then the type inside it MUST be a TypeScript type,

or else TypeScript will ignore the type and define the parameter to be

any, which meanas that it is typeless.

This is not going to be a tutorial on JSDoc. If you want more information, there’ll be a link

to the JSDoc documentation in the TypeScript site. Because, yes, TypeScript supports JSDoc. How?

Well, once this function is JSDoc-ed, then for all sense and purpose, TypeScript will treat it as

typed. Let’s add another file that uses the add function, and see how it supports it.

const {add} = require('./utils')

console.log(add(4, 5)) // => 9The above code imports the add function and calls it. Nothing special here. But! If you’re using

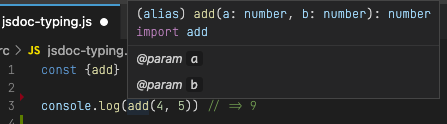

Visual Studio Code (and probably other IDEs as well), and hover above the add function, you’ll

get this:

So Visual Studio Code, because it supports TypeScript out of the box, shows the JSDoc information. But moreover, because TypeScript is reading the JSDoc, it’s also reading the JavaScript code as if it was TypeScript, figuring out by itself that the return value is also a number, and showing that information as well! Without us have to add type information about the return value.

Adding type checking to the hover information #

This is already great! We get nice autocompletion and hover information for our functions. But it’s not typechecking. It doesn’t fail if the types are incorrect. It doesn’t even show up in Visual Studio Code as an error. Let’s try it and see:

const {add} = require('./utils')

console.log(add('sdfsdf', 5)) // => This shouldn't pass type checking

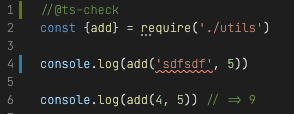

console.log(add(4, 5)) // => 9If you try it in Visual Studio code, you won’t get a squiggly red line on the second line where

we pass a string argument. But there is a way to do that, a shortcut to the correct way. I’ll show

you how to do it. We’ll just add a //@ts-check to the start of the code:

//@ts-check

const {add} = require('./utils')

console.log(add('sdfsdf', 5))

console.log(add(4, 5)) // => 9Let’s now see it in Visual Studio Code:

Wow! Types are working! I can now see my errors! Typescript just typechecked my file. Yes, it’s not failing the build or the tests yet, but wait for it…

Implicit and explicit typing #

Let’s define a variable that accepts the return of the call to add:

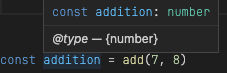

const addition = add(7, 8)What will be the type of this variable? TypeScript does it’s thing, and the type will

be number, because TypeScript knows how to automatically infer the type of the variable.

To prove that it does, let’s hover above the new variable:

This has nothing to do with JSDoc: it’s TypeScript implicitly typing the variable to the correct type. But what if we wanted the type to be explicit? What if we wanted the JSDoc equivalent of this TypeScript code?

const addition: number = add(7, 8)We still can. The equivalent JSDoc is this:

/**@type {number} */

const addition = add(7, 8)@type in the line before types the variable to whatever you want it to be, explicitly.

The nice thing about TypeScript is that you usually don’t need to type things explicitly as it

can infer the type of the variable automatically.

Running typechecking as a test #

To add real typechecking, one that will fail the build, and not just show up in Visual Studio Code, we need to add TypeScript to our package. Let’s do that:

npm install --save-dev typescriptGreat, we’ve installed TypeScript. Let’s now run typechecking on our files:

$ npx tsc --noEmit --allowJS src/*.js

src/jsdoc-typing.js:4:17 - error TS2345: Argument of type 'string' is not assignable to parameter of type 'number'.

4 console.log(add('sdfsdf', 5))

~~~~~~~~

Found 1 error.Yup, we found the error using TypeScript, and it failed the build. We’ve just completed step 1 of our JSDoc typing journey.

A few comments on the options we gave to TypeScript:

--noEmit: this tells TypeScript not to transpile to “JavaScript”. Obviously, we don’t need that, because our files are already JavaScript.--allowJs: this tells TypeScript that it’s OK to check JavaScript files. If we don’t add this, it will ignore the JS files, even if we specified them in the command line.

Configuring TypeScript options correctly #

If we want to be serious about TypeScript, we need to configure it like the pros. To do that,

we add a tsconfig.json to our project root. We’ll build this file slowly, understanding

each step:

{

"include": ["src/**/*.js"],

"exclude": ["node_modules"]

}First, we define which files we want to type check, and which we don’t. This is pretty

self-explanatory, and you may need to change this to conform to where your JS files are.

And, yes, you do need to tell TypeScript to ignore node_modules, because otherwise it won’t and

you will get i) long typechecking times, and ii) lots of errors in packages you don’t care about.

Let’s continue:

{

"compilerOptions": {

"lib": ["es2020", "DOM"],

"moduleResolution": "node",

"module": "CommonJS",

},

"include": ["src/**/*.js", "src/**/*.d.ts"],

"exclude": ["node_modules"]

}These new options defines the source code that it will get. We’re telling it that it’s going

to use the latest JavaScript defitions, and that we’re using CommonJS. Oh, and the DOM is

so that it recognizes console.log.

Let’s continue with the options that allow us to use JS files:

{

"compilerOptions": {

"...": "...",

"allowJs": true,

"checkJs": true,

"resolveJsonModule": true,

"noEmit": true.

},

"...": "..."

}allowJsallows JS files to be typecheckedcheckJstells TypeScript to check all JavaScript files, and not just those with//@ts-checkresolveJsonModuletells Typescript thatrequire-ing.jsonfiles is OK. It will even generate a type for the JSON in the file, so it will be typechecked correctly. Because we’re using JavaScript, andrequire-ing JSON in JavaScript is fine, we turn this on.noEmittells TypeScript not to emit transpiled files, which we don’t really want because we already have our JavaScript files.

Last, but not least, we have our regular TypeScript configurations. Let’s go all in, and use the strictest option, which tells TypeScript to do the strictest checks:

{

"compilerOptions": {

"...": "...",

"strict": true

},

"...": "..."

}If you want less strict options, or any other TypeScript configuration, feel free to add them here.

This produces our final tsconfig.json:

{

"compilerOptions": {

"lib": ["es2020", "DOM"],

"moduleResolution": "node",

"module": "esnext",

"resolveJsonModule": true,

"allowJs": true,

"checkJs": true,

"noEmit": true,

"strict": true

},

"include": ["src/**/*.js"],

"exclude": ["node_modules"]

}Now we can have TypeScript be part of our tests by adding it to our scripts in package.json:

{

"scripts": {

"test": "mocha/jest ... && tsc"

}

}Now, when we run npm test, Typescript (tsc) will run, look at our JSDoc typings,

and typecheck all our JS files.

We’ve got TypeScript, but without the transpilation. Amazing, no?

Typedefs, classes, and importing types #

Sure, but how much of TypeScript do we have? Do we have interface Foo {}? type Foo = ...?

class? We do! We’ll get to interface later, but let’s start with type Foo = ....

We’ll define a function, breakName, that breaks a full name to the “first name” and “last name”.

(Please don’t use this code in production, as it’s an extremely naïve implementation):

function breakName(name) {

const [first, ...rest] = name.split(' ')

return {firstName: first, lastName: rest.join(' ')}

}Since I’m using Visual Studio Code, when I write the above code, I get a nice squiggly red line

on the name parameter:

This is because I use strict: true in the tsconfig.json, and that tells TypeScript that

implicitly typing variables to any is not allowed, and thus forces you to define all function

parameters. So let’s fix that, and as long as we’re there, let’s define the return value too:

/**

* @param {string} name

*

* @returns { {firstName: string, lastName: string} }

*/

function breakName(name) {

const [first, ...rest] = name.split(' ')

return {firstName: first, lastName: rest.join(' ')}

}We defined the {firstName: string, lastName: string} as a return value. As I said:

you have the full power of Typescript at your disposal. Notice the double curly braces {{...}}

when defining the return type. The outer curly braces are needed by JSDoc, whose syntax

forces us to surround all types with curly braces, and the inner curly braces are for the TypeScript

type definition for an object.

Let’s make it nicer, to make that return value a type? We can do that, using

the @typedef JSDoc:

/**

*

* @typedef { {firstName: string, lastName: string} } BrokenName

*/This is equivalent to the TypeScript code:

type BrokenName = {firstName: string, lastName: string}To use it in the function, we change it a bit:

/**

* @param {string} name

*

* @returns {BrokenName}

*/

function breakName(name) {

const [first, ...rest] = name.split(' ')

return {firstName: first, lastName: rest.join(' ')}

}And to use it, we just:

const brokenName = breakName('Gil Tayar')

console.log(brokenName) // => { firstName: 'Gil', lastName: 'Tayar' }Importing types from other modules #

What if we wanted to do explicit typings in the above example? As above, we can just do this:

/**@type {BrokenName} */

const brokenName = breakName('Gil Tayar')But what happens if breakName and BrokenName come from another file? In TypeScript we can use:

import {BrokenName} from './names'

const brokenName: BrokenName = breakName('Gil Tayar')But this is not possible in JavaScript, because JavaScript modules don’t export types. So how

do we do the same in JSDoc? How do we use a type (or interface or class) that was defined in another

module? The answer is “use import(type)”:

/**@type {import('./names').BrokenName} */

const brokenName = breakName('Gil Tayar')The import in JSDoc allows you to import “types stuff” from other modules and packages. And

if you get tired of writing import('./names') everywhere, you can always write…

/**@typedef {import('./names').BrokenName} BrokenName */…to alias it in your other module.

Using types from other NPM packages #

Would this import work with other NPM pacakges? Definitely! Let’s talk about using types from

another NPM package. We have three different types of Packages:

- Packages that have type information, especially packages that were written in TypeScript

- Packages that have external type information from a

@types/...package - Packages that don’t have type information

Let’s talk about each one, and how to use each.

Using types from libraries that have type information #

This one’s easy: just npm install the package and use it. If it has type information,

TypeScript will find it, don’t worry. Just use the stuff that are exported, and it will have

type information in it. Let’s take an example:

const slugify = require('@sindresorhus/slugify')

console.log(slugify('i ❤️ slugs')) // => i-slugsWe can even use the types that the library exports:

/**@type {import('@sindresorhus/slugify').Options} */

const slugifyOptions = {separator: '_'}

console.log(slugify('i ❤️ slugs', slugifyOptions)) // => i_slugsAnd if there’s a typechecking error, TypeScript will fail. So for this code:

slugify('something', {badOption: true})Then the failure will be:

$ npm test

src/jsdoc-typing.js:39:23 - error TS2345: Argument of type '{ badOption: boolean; }' is not assignable to parameter of type 'Options'.

Object literal may only specify known properties, and 'badOption' does not exist in type 'Options'.

39 slugify('something', {badOption: true})

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~It works! We can use any TypeScript compatible library and use it and get the same typechecking that TypeScript programs use.

Using types from libraries that have external type information from a @types/... package #

Let’s try Lodash:

const {map} = require('lodash')If we typecheck this, we get:

$ npm test

src/jsdoc-typing.js:5:23 - error TS7016: Could not find a declaration file for module 'lodash'. '/Users/giltayar/code/jsdoc-typing/node_modules/lodash/lodash.js' implicitly has an 'any' type.

Try `npm i --save-dev @types/lodash` if it exists or add a new declaration (.d.ts) file containing `declare module 'lodash';`

5 const {map} = require('lodash')

~~~~~~~~Weird error. It says (if I may interpret), that it couldn’t find type information for lodash.

And it won’t continue without types. What can we do?

Theoretically, we can write the type declarations ourselves, but that’s a lot of work, and we’ll see how to do it below. But another option is to use an existing, community-owned, database of type definitions for lots of NPM packages. Let’s see if Lodash has type definitions in this database. To find out, just add a package that has these type definitions:

npm install --save-dev @types/lodashIt works! If a package has type information that is community-owned, it is probably in

@types/<package-name>, and if you install it, you will get typechecking on that library.

Now if we typecheck the file, we find we have type definitions for the map function we imported.

Yay!

Using types from libraries that don’t have type information #

Let’s try another NPM package. This time, this package doesn’t have type information embedded in it, and doesn’t have a community-built type package for it. As an example, we’ll use the package… flowers: It’s a package that lists about 400 different types of flowers, and is a proof that you can find anything in the NPM registry!

And obviously it doesn’t have a @types type package:

$ npm i @types/flowers

npm ERR! code E404

npm ERR! 404 Not Found - GET https://registry.npmjs.org/@types%2fflowers - Not found

...So what happens when we add it to our code:

const flowers = require('flowers')Let’s typecheck it: as expected, we get an error because TypeScript wants type definitions for the module:

$ npm test

src/jsdoc-typing.js:6:25 - error TS7016: Could not find a declaration file for module 'flowers'. '/Users/giltayar/code/jsdoc-typing/node_modules/flowers/index.js' implicitly has an 'any' type.

Try `npm i --save-dev @types/flowers` if it exists or add a new declaration (.d.ts) file containing `declare module 'flowers';`

6 const flowers = require('flowers')

~~~~~~~~~If we were working in TypeScript, the solution would be simple: add a declare module 'flowers'

somewhere in our TypeScript code. This signals to TypeScript that the module exists,

and there are no type definitions for it, so anything coming out of it is just any. Of

course, we could go the extra mile, and even define the types for this module using:

declare module 'flowers' {

// ... type definitions

}But we don’t have TypeScript code. And we don’t want TypeScript code, because we don’t want to do

transpile. And there’s no equivalent to declare module... in JSDoc. But there is another

solution: .d.ts files. These are TypeScript “declaration files” that describe the types and API

of a module, and are actually what is exported by packages when they have type definitions,

and is what is exported by those type definition packages in the @types/... repository. They

include only type definitions, and have no executable code in them.

And we can use them by having a few of those in our project. So we create a file, let’s call it

global.d.ts, and add the declare module 'flowers' there:

// src/global.d.ts

declare module 'flowers'That is not enough, though. We need the TypeScript type checker to know about this file, so

we need to include it in the tsconfig.json:

{

"...": "",

"include": ["src/**/*.js", "src/**/*.d.ts"],

"exclude": "..."

}By adding src/**/*.d.ts, we tell TypeScript to add global.d.ts to the type checking, and now

if we type check our file using npm test, it completes with no error.

.d.ts files are a nice escape hatch because you can use any type script type definitions in them.

We’ll be using them later for some advanced TypeScript stuff.

Advanced Typescript #

Can we do other, more advanced stuff that we can do in TypeScript? Yes! Almost everything

you can do in TypeScript, you can do with JSDoc. Let’s start with class

Class type definitions #

class Person {

/**@type {string}*/

firstName

/**@type {string}*/

lastName

/**

* @param {string} firstName

* @param {string} lastName

*/

constructor(firstName, lastName) {

this.firstName = firstName

this.lastName = lastName

}

/**

* @returns {string}

*/

fullName() {

return `${this.firstName} ${this.lastName}`

}

}The above is a class Person, with two properties (firstName and lastName) and a method

(fullName()), that are all typechecked. We didn’t really use any new JSDoc capabilities,

just the regular @type, @param, and @return. But since it’s inside a class, TypeScript

knows how to deal with it, and can typecheck it. So the following bad code…

const p1 = new Person('Gil', 'Tayar')

p1.someName

p1.fullName(4)…will fail typechecking:

$ npm t

src/jsdoc-typing.js:50:4 - error TS2339: Property 'someName' does not exist on type 'Person'.

50 p1.someName

~~~~~~~~

src/jsdoc-typing.js:51:13 - error TS2554: Expected 0 arguments, but got 1.

51 p1.fullName(4)

~Type Casting #

In TypeScript, we sometimes need to cast something, to tell the typechecker that we know that the thing is of a certain type. As an example, take this example:

const numberOrString = Math.random() <= 1 ? "This is a string" : 100;

console.log(numberOrString.toUpperCase())The typechecker will fail on numberOrString.toUpperCase() because TypeScript

correctly infers the type of numberOrString to be number | string. And yet, we know

that the type of numberOrString is always string because Math.random() always returns a

number in the range 0…1. If we were in TypeScript, we could write:

const numberOrString = Math.random() <= 1 ? "This is a string" : 100;

console.log((numberOrString as string).toUpperCase())Does JSDoc have a comparable mechanism? The answer is yes:

const numberOrString = Math.random() <= 1 ? "This is a string" : 100;

console.log(/**@type {string}*/(numberOrString).toUpperCase()))We’ve already seen that @type can define the type of a variable. Here we see that @type can

define the type of an _expression. Notice that the expression MUST be surrounded by parentheses,

otherwise the @type won’t know what expression is to be cast.

This is the ugliest part of JSDoc, and I truly wish there was a nicer way of typecasting, but there isn’t any unfortunately. It’s the only place in JSDoc land that I really dislike.

Generics #

Now for the craziest thing in JSDoc: you can even do generics. Let’s go wild. Let’s write

a function, mapValue, that receives an object and a map function, and returns an object

where the keys are the same, but the values are mapped:

function mapValues(object, mapFunction) {

return Object.fromEntries(Object.entries(object).map(([key, value]) => [key, mapFunction(value)]))

}Nice and simple. Let’s add types, but without generics, using the any type:

/**

* @param {Record<any, any>} object

* @param {(t: any) => any} mapFunction

*

* @returns {Record<any, any>}

*/

function mapValues(object, mapFunction) {

return Object.fromEntries(Object.entries(object).map(([key, value]) => [key, mapFunction(value)]))

}(Record is a builtin type in TypeScript, and defines an object with key type and value tyep).

Better than before, because we know that the first parameter needs to be an object,

and the second one a mapping function.

But if we write this code:

const result = mapValue({a: 4}, x => x + 1)

result.xTypeScript won’t catch us on the second line, even though it’s obvious that result shouldn’t have

an x property.

If we were in TypeScript land, we would write something like this:

<K extends string|number|symbol, T, W> function (obj: Record<K, T>, mapFunction: (t: T) => W): Record<K, W> {

//...

}Is there an equivalent in JSDoc? Incredibly enough, there is:

/**

* @template {string|number|symbol} K

* @template T

* @template W

* @param {Record<K, T>} object

* @param {(t: T) => W} mapFunction

*

* @returns {Record<K, W>}

*/

function mapValues(object, mapFunction) {

return Object.fromEntries(Object.entries(object).map(([key, value]) => [key, mapFunction(value)]))

}This is the equivalent to the above TypeScript generic code: three generic variables

(K, T, and W), where K also extends string|number|symbol, and the parameters

are defined according to those generic parameters. And now, if we use the function incorrectly…

const result = mapValue({a: 4}, x => x + 1)

result.x

// ~

//Property 'x' does not exist on type 'Record<"a", number>'…we get the correct error.

There’s just one small problem: mapValues itself doesn’t typecheck. Typescript’s internal

definition for Object.fromEntries/entries doesn’t return the correct types and resets

them to a generic (Record<any, any>) which makes TypeScript (rightfully) fail

the typechecking because the return type of mapValue is more specific.

Two options: typecast it, or just ignore the error. This time, I’ll ignore the error:

function mapValues(object, mapFunction) {

//@ts-ignore

return Object.fromEntries(Object.entries(object).map(([key, value]) => [key, mapFunction(value)]))

}The //@ts-ignore tells TypeScript to ignore the TypeScript errors in the line following

the comment. Use it, but use it sparingly. An even better option, in my opinion, is the companion

@ts-expect-errpr:

function mapValues(object, mapFunction) {

//@ts-expect-error

return Object.fromEntries(Object.entries(object).map(([key, value]) => [key, mapFunction(value)]))

}This will ignore any typechecking failures in the next line, but will fail the typecheck if there are no errors. It’s a good way to ensure that that the ignoring is really needed.

Using a bit of TypeScript typings #

We’ve seen that most everything you can do in TypeScript, you can do in JavaScript with JSDocs,

and get full typechecking. But there are some things we can do in TypeScript that are

not (yet?) possible using JSDoc typings. One example is, incredibly enough, interface: you can

define a type alias to an interface, but you can’t define an interface. So the equivalent of

type Point = {x: number, y: number}Would be

/**

* @typedef { {x: number, y: number} } Point

*/But there is no equivalent in JSDoc to

interface Point {

x: number,

y: number

}So what do we? While we can get by with only type aliases, it would be nice

to be able to declare an interface. And it turns out that we can: we’ll use a new

.d.ts file to define the interface Point, and then use import to use it. Let’s

start with the type definition:

// point-type.d.ts

export interface Point {

x: number

y: number

}And now, since we’ve already told TypeScript to include *.d.ts files in the typechecking, we

can use it in our JavaScript code:

/**

* @param {import('./point-type').Point} point

* @param {number} dx

* @param {number} dy

*

* @returns {import('./point-type').Point}

*/

function move(point, dx, dy) {

return {x: point.x + dx, y: point.y + dy}

}

console.log(move({x: 2, y: 4}, 1, 1)) // ==> { x: 3, y: 5 }We’ve used import('./point-type).Point to “get” the exported type, and used it in our regular

JSDoc code. Mission accomplished!

Note: you cannot use

declare moduleandexportin the same.d.tsfile (for some arcane reason I can’t understand), so you need at least two separate.d.tsfiles if you want bothdeclare module ...andexport ....

Exporting .d.ts files #

The last functionality that we have in TypeScript, and which we would like to duplicate using

JSDoc typing, is the ability to generate an NPM package that also exposes its type definitions.

Just like slugify does above. It’s actually possible, and even easy. Let’ start on the journey.

First, we need to generate the .d.ts file that will contain all the type definitions we have.

We’ll run it in a build script, because that is what it is: building the definition files

from source. This build script doesn’t need to be run in development, but it does need to be

run before we publish the package to NPM. This is how it will look like:

"scripts": {

"build": "tsc --noEmit false --emitDeclarationOnly true",

"test": "tsc",

"start": "node src/jsdoc-typing.js"

}We’re adding two options when running tsc because we do want to emit files (--noEmit false),

but want to emit only .d.ts files (--emitDeclarationOnly true).

We also need to tell TypeScript where to emit the .d.ts files,

and we do so in the tsconfig.json:

{

"...": "",

"compilerOptions": {

"...": "",

"declarationDir": "types",

"declaration": true

}

}This tells TypeScript to generate the declarations into the types directory. We also need to make

sure that when we publish this package, the types directory will also be published, so

if you’re whitelisting the files you publish by using files in package.json, don’t forget

to add the types directory there:

{

"files ": ["src", "types"]

}And, while we’re at it, we don’t really want the types directory to be source-controlled,

because it’s a file that generated by source code, so we add it to .gitignore:

# .gitignore

node_modules

typesLast thing we need to do before we publish this package, is add a property in the package.json

that specifies where the root .d.ts file is, so that any package that npm install-s this package

will know how to get at its type definitions. We define this using the "types" property:

{

"name": "jsdoc-typing-example",

"main": "./src/jsdoc-typing.js",

"types": "./types/jsdoc-typing.d.ts",Just like you define the package’s entry point using main, so you define your package’s type

definition entry point using types. And we generated this.d.ts using the npm run build

script we created earlier, and with the help of the tsconfig.json properties we added

which told it where to generate those type definition files. Phew!

One last fine tune #

One last thing. Remember those .d.ts files we wrote manually? global.d.ts and point-type.d.ts?

Well, it seems TypeScript forgot to copy them to the types directory

(is this a bug? I think it is), so we’ll have to do it ourselves in our build script:

"scripts": {

"build": "tsc --noEmit false --emitDeclarationOnly true && cp src/*.d.ts types",

}Publishing the package and using it’s type definions #

Once we npm publish this package, we can use it in any JS (or TS) file, and it will enable

code completion and typeching of the available exports:

//@ts-check

const example = require('jsdoc-typing-example')

example.add('wrong-type', 4)

// ~~~~~~~~~~~~Mission accomplished!

Drawbacks #

Are there any drawbacks to this method? Yes, of course there are. The four I can think of are:

- The type definitions in JSDoc comments are sometimes clumsy and verbose

- You can’t do everything with those type definitions, and while there is a solution for that

(using

.d.tsfiles as described above), it feels like a kludge - The type casting syntax is very clumsy and is a wart on the code. And unlike the JSDoc comments, it sits right inside your code

- There isn’t a lot of experience using JSDoc typings out there. Hopefully, this blog post will change that.

Summary #

But weighing the drawbacks, I still feel that this is a better solution than TypeScript transpiling. You can use JSDoc typing to do everything you can do with TypeScript, but with pure JavaScript and without any transpilation, while using the ability of TypeScript to read type definitions encoded in JSDoc comments, and thus enable embedding type information in your JavaScript files, and using that type information to typecheck your JS files, as if they were TypeScript.

So go ahead and use JSDoc typings: all the benefits of TypeScript, without the drawbacks!

References #

- Great documentation on JSDoc comments on the Typescript site: https://www.typescriptlang.org/docs/handbook/jsdoc-supported-types.html

- The Github repo with the sample code above, and a complete example of such a JSDoc package: https://github.com/giltayar/jsdoc-typing

- TSConfig.json reference: https://www.typescriptlang.org/tsconfig